what is a faction according to federalist 10

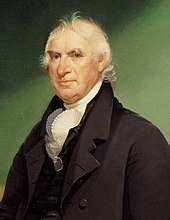

James Madison, author of Federalist No. 10 | |

| Author | James Madison |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Series | The Federalist |

| Publisher | Daily Advertiser |

| Publication date | November 22, 1787 |

| Media blazon | Newspaper |

| Preceded by | Federalist No. nine |

| Followed by | Federalist No. 11 |

Federalist No. 10 is an essay written past James Madison every bit the tenth of The Federalist Papers, a series of essays initiated by Alexander Hamilton arguing for the ratification of the United states Constitution. Published on Nov 22, 1787, under the proper noun "Publius", Federalist No. 10 is among the most highly regarded of all American political writings.[1]

No. 10 addresses the question of how to reconcile citizens with interests contrary to the rights of others or inimical to the interests of the customs equally a whole. Madison saw factions as inevitable due to the nature of man—that is, as long as people concord differing opinions, have differing amounts of wealth and own differing amount of property, they will continue to form alliances with people who are well-nigh like to them and they will sometimes work confronting the public interest and infringe upon the rights of others. He thus questions how to guard confronting those dangers.[ commendation needed ]

Federalist No. 10 continues a theme begun in Federalist No. nine and is titled "The Utility of the Union as a Safeguard Against Domestic Faction and Coup". The whole series is cited past scholars and jurists every bit an authoritative estimation and explication of the significant of the Constitution. Historians such as Charles A. Beard argue that No. 10 shows an explicit rejection by the Founding Fathers of the principles of direct democracy and factionalism, and contend that Madison suggests that a representative democracy is more effective against partisanship and factionalism.[2] [3]

Madison saw the federal Constitution as providing for a "happy combination" of a democracy and a purer democracy, with "the great and amass interests being referred to the national, the local and particular to the Land legislatures" resulting in a decentralized governmental structure. In his view, this would brand it "more difficult for unworthy candidates to practice the vicious arts by which elections are too often carried."

Background [edit]

Prior to the Constitution, the thirteen states were bound together by the Manufactures of Confederation. These were, in essence, a military alliance between sovereign nations adopted to better fight the Revolutionary War. Congress had no ability to tax, and equally a event, was non able to pay debts resulting from the Revolution. Madison, George Washington, Benjamin Franklin and others feared a suspension-upwards of the union and national defalcation.[4] Like Washington, Madison felt the revolution had non resolved the social problems that had triggered information technology, and the excesses ascribed to the Male monarch were now being repeated by the country legislatures. In this view, Shays' Rebellion, an armed insurgence in Massachusetts in 1786, was simply one, albeit farthermost, example of "autonomous backlog" in the aftermath of the War.[v]

A national convention was called for May 1787, to revise the Articles of Confederation. Madison believed that the trouble was not with the Articles, but rather the state legislatures, and so the solution was not to fix the articles simply to restrain the excesses of united states. The main questions before the convention became whether the states should remain sovereign, whether sovereignty should exist transferred to the national government, or whether a settlement should residual somewhere in between.[v] By mid-June, it was clear that the convention was drafting a new plan of government around these issues—a constitution. Madison's nationalist position shifted the debate increasingly away from a position of pure state sovereignty, and toward the compromise.[6] In a debate on June 26, he said that government ought to "protect the minority of the opulent confronting the majority" and that unchecked, democratic communities were subject to "the turbulency and weakness of unruly passions".[vii]

Publication [edit]

Paul Leicester Ford's summary preceding Federalist No. x, from his 1898 edition of The Federalist

September 17, 1787 marked the signing of the concluding document. By its own Article 7, the constitution drafted past the convention needed ratification by at to the lowest degree nine of the thirteen states, through special conventions held in each country. Anti-Federalist writers began to publish essays and letters arguing against ratification,[8] and Alexander Hamilton recruited James Madison and John Jay to write a serial of pro-ratification letters in response.[ix]

Like well-nigh of the Federalist essays and the vast majority of The Federalist Papers, No. 10 showtime appeared in popular newspapers. Information technology was first printed in the Daily Advertiser under the proper noun adopted by the Federalist writers, "Publius"; in this information technology was remarkable amidst the essays of Publius, as almost all of them showtime appeared in one of 2 other papers: the Independent Periodical and the New-York Parcel. Federalist No. 37, also by Madison, was the but other essay to appear get-go in the Advertiser.[10]

Considering the importance later ascribed to the essay, information technology was reprinted simply on a limited calibration. On November 23, information technology appeared in the Package and the next twenty-four hours in the Contained Journal. Exterior New York Urban center, it fabricated 4 appearances in early on 1788: January 2 in the Pennsylvania Gazette, Jan 10 in the Hudson Valley Weekly, January fifteen in the Lansingburgh Northern Centinel, and January 17 in the Albany Gazette. Though this number of reprintings was typical for The Federalist essays, many other essays, both Federalist and Anti-Federalist, saw much wider distribution.[xi]

On January 1, 1788, the publishing visitor J. & A. McLean appear that they would publish the start 36 of the essays in a single volume. This volume, titled The Federalist, was released on March 2, 1788. George Hopkins' 1802 edition revealed that Madison, Hamilton, and Jay were the authors of the series, with two later printings dividing the work by author. In 1818, James Gideon published a tertiary edition containing corrections by Madison, who by that time had completed his two terms as President of the United states of america.[12]

Henry B. Dawson's edition of 1863 sought to collect the original newspaper articles, though he did not always find the first instance. It was much reprinted, admitting without his introduction.[13] Paul Leicester Ford's 1898 edition included a tabular array of contents which summarized the essays, with the summaries once again used to preface their respective essays. The first date of publication and the newspaper proper noun were recorded for each essay. Of modern editions, Jacob East. Cooke'due south 1961 edition is seen every bit authoritative, and is nigh used today.[14]

The question of faction [edit]

Federalist No. ten continues the discussion of the question broached in Hamilton's Federalist No. 9. Hamilton at that place addressed the subversive role of a faction in breaking apart the republic. The question Madison answers, then, is how to eliminate the negative effects of faction. Madison defines a faction as "a number of citizens, whether amounting to a minority or bulk of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adverse to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and amass interests of the community."[15] He identifies the most serious source of faction to be the variety of opinion in political life which leads to dispute over fundamental problems such as what regime or religion should be preferred.

Madison argues that "the most common and durable source of factions has been the various and unequal distribution of property."[16] He states, "Those who hold and those who are without property accept e'er formed distinct interests in gild."[16] Providing some examples of the distinct interests, Madison identified a landed interest, a manufacturing interest, a mercantile interest, a moneyed interest, and "many bottom interests".[16] Madison insists that they all belonged to "different classes" that were "actuated by unlike sentiments and views."[16] Thus, Madison argues, these dissimilar classes would be prone to make decisions in their own interest, and not for the public good. A law regarding private debts, for instance, would be "a question to which the creditors are parties on one side, and the debtors on the other." To this question, and to others like it, Madison notes that, though "justice ought to concord the balance betwixt them," the interested parties would reach different conclusions, "neither with a sole regard to justice and the public practiced."

Like the anti-Federalists who opposed him, Madison was substantially influenced by the work of Montesquieu, though Madison and Montesquieu disagreed on the question addressed in this essay. He likewise relied heavily on the philosophers of the Scottish Enlightenment, particularly David Hume, whose influence is near clear in Madison'southward discussion of the types of faction and in his argument for an extended democracy.[17] [18]

Madison's arguments [edit]

Madison start theorizes that in that location are two ways to limit the damage caused by faction: either remove the causes of faction or command its effects. He then describes the two methods to remove the causes of faction: first, destroying liberty, which would work because "freedom is to faction what air is to burn",[19] just it is incommunicable to perform considering liberty is essential to political life, just as air is "essential to animate being life." After all, Americans fought for it during the American Revolution. The second option, creating a club homogeneous in opinions and interests, is impracticable. The diversity of the people's power is what makes them succeed more or less, and inequality of property is a right that the regime should protect. Madison peculiarly emphasizes that economic stratification prevents everyone from sharing the same opinion. Madison concludes that the impairment acquired by faction can be limited only by controlling its effects.

He then argues that the only problem comes from bulk factions because the principle of popular sovereignty should foreclose minority factions from gaining power. Madison offers two ways to bank check majority factions: prevent the "being of the same passion or interest in a majority at the same fourth dimension" or render a bulk faction unable to human action.[twenty] Madison concludes that a small democracy cannot avert the dangers of majority faction because small size ways that undesirable passions tin can very easily spread to a bulk of the people, which can then enact its will through the democratic government without difficulty.

Madison states, "The latent causes of faction are thus sown in the nature of homo",[21] so the cure is to control their furnishings. He makes an argument on how this is not possible in a pure democracy but possible in a republic. With pure democracy, he means a organisation in which every citizen votes directly for laws (direct democracy), and, with republic, he intends a society in which citizens elect a small torso of representatives who so vote for laws (representative democracy). He indicates that the phonation of the people pronounced by a body of representatives is more conformable to the interest of the customs, since, again, mutual people's decisions are afflicted by their self-involvement.

He then makes an argument in favor of a large commonwealth against a small-scale republic for the choice of "fit characters"[22] to represent the public's voice. In a large republic, where the number of voters and candidates is greater, the probability to elect competent representatives is broader. The voters have a wider choice. In a small democracy, it would also be easier for the candidates to fool the voters but more difficult in a big one. The concluding argument Madison makes in favor of a large commonwealth is that equally, in a minor republic, there will be a lower diversity of interests and parties, a majority will more than frequently exist found. The number of participants of that bulk will exist lower, and, since they live in a more limited territory, it would be easier for them to concur and work together for the accomplishment of their ideas. While in a large republic the variety of interests will be greater and so to brand it harder to find a majority. Fifty-fifty if there is a bulk, it would be harder for them to work together because of the big number of people and the fact they are spread out in a wider territory.

A commonwealth, Madison writes, is different from a democracy because its government is placed in the hands of delegates, and, as a result of this, it tin be extended over a larger expanse. The idea is that, in a large democracy, there will be more "fit characters" to choose from for each delegate. Besides, the fact that each representative is chosen from a larger constituency should make the "vicious arts" of electioneering[22] (a reference to rhetoric) less effective. For instance, in a large republic, a corrupt delegate would need to bribe many more people in order to win an election than in a pocket-size republic. Besides, in a commonwealth, the delegates both filter and refine the many demands of the people and then as to prevent the type of frivolous claims that impede purely autonomous governments.

Though Madison argued for a large and diverse republic, the writers of the Federalist Papers recognized the need for a residue. They wanted a commonwealth diverse enough to preclude faction but with enough commonality to maintain cohesion among the states. In Federalist No. ii, John Jay counted as a blessing that America possessed "ane united people—a people descended from the same ancestors, the same language, professing the same religion".[23] Madison himself addresses a limitation of his conclusion that large constituencies will provide better representatives. He notes that if constituencies are as well large, the representatives will be "also petty acquainted with all their local circumstances and lesser interests".[22] He says that this problem is partly solved past federalism. No matter how large the constituencies of federal representatives, local matters will be looked afterward by state and local officials with naturally smaller constituencies.

Contemporaneous counterarguments [edit]

George Clinton, believed to be the Anti-Federalist writer Cato

The Anti-Federalists vigorously contested the notion that a democracy of diverse interests could survive. The writer "Cato" (another pseudonym, most likely that of George Clinton)[24] summarized the Anti-Federalist position in the commodity Cato no. 3:

Whoever seriously considers the immense extent of territory comprehended within the limits of the Us, with the variety of its climates, productions, and commerce, the divergence of extent, and number of inhabitants in all; the dissimilitude of involvement, morals, and policies, in almost every 1, volition receive information technology as an intuitive truth, that a consolidated republican form of regime therein, can never grade a perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of freedom to you and your posterity, for to these objects it must be directed: this unkindred legislature therefore, composed of interests reverse and different in their nature, will in its exercise, emphatically be, similar a house divided against itself.[25]

Mostly, information technology was their position that republics about the size of the individual states could survive, but that a republic on the size of the Union would fail. A particular point in support of this was that well-nigh of the states were focused on one industry—to generalize, commerce and shipping in the northern states and plantation farming in the southern. The Anti-Federalist conventionalities that the wide disparity in the economic interests of the various states would atomic number 82 to controversy was perhaps realized in the American Civil War, which some scholars aspect to this disparity.[26] Madison himself, in a letter to Thomas Jefferson, noted that differing economic interests had created dispute, fifty-fifty when the Constitution was being written.[27] At the convention, he specially identified the distinction betwixt the northern and southern states as a "line of discrimination" that formed "the real deviation of interests".[28]

The word of the platonic size for the republic was not limited to the options of individual states or encompassing wedlock. In a letter of the alphabet to Richard Price, Benjamin Rush noted that "Some of our enlightened men who brainstorm to despair of a more complete marriage of the States in Congress have secretly proposed an Eastern, Middle, and Southern Confederacy, to be united by an alliance offensive and defensive".[29]

In making their arguments, the Anti-Federalists appealed to both historical and theoretic evidence. On the theoretical side, they leaned heavily on the work of Charles de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu. The Anti-Federalists Brutus and Cato both quoted Montesquieu on the issue of the platonic size of a republic, citing his statement in The Spirit of the Laws that:

It is natural to a republic to have just a small-scale territory, otherwise it cannot long subsist. In a large democracy in that location are men of big fortunes, and consequently of less moderation; at that place are trusts too nifty to be placed in any single subject; he has interest of his ain; he soon begins to think that he may exist happy, bully and glorious, past oppressing his fellow citizens; and that he may raise himself to grandeur on the ruins of his state. In a big commonwealth, the public good is sacrificed to a thousand views; it is subordinate to exceptions, and depends on accidents. In a minor one, the involvement of the public is easier perceived, better understood, and more than within the reach of every denizen; abuses are of less extent, and of course are less protected.[30]

Greece and Rome were looked to every bit model republics throughout this debate,[31] and authors on both sides took Roman pseudonyms. Brutus points out that the Greek and Roman states were small, whereas the U.S. is vast. He also points out that the expansion of these republics resulted in a transition from costless regime to tyranny.[32]

Modern analysis and reaction [edit]

In the first century of the American republic, No. x was not regarded as amongst the more than important numbers of The Federalist. For instance, in Democracy in America, Alexis de Tocqueville refers specifically to more than fifty of the essays, but No. x is non amidst them.[33] Today, however, No. 10 is regarded every bit a seminal piece of work of American democracy. In "The People'south Vote", a popular survey conducted by the National Archives and Records Administration, National History Solar day, and U.Due south. News and World Report, No. x (along with Federalist No. 51, also past Madison) was called as the 20th almost influential document in Usa history.[34] David Epstein, writing in 1984, described it as among the virtually highly regarded of all American political writing.[35]

The historian Charles A. Bristles identified Federalist No. 10 as one of the most of import documents for understanding the Constitution. In his volume An Economical Interpretation of the Constitution of the The states (1913), Beard argued that Madison produced a detailed caption of the economic factors that lay behind the creation of the Constitution. At the outset of his study, Bristles writes that Madison provided "a masterly statement of the theory of economic determinism in politics" (Beard 1913, p. 15). Later in his study, Beard repeated his indicate, providing more than emphasis. "The most philosophical examination of the foundations of political science is fabricated past Madison in the tenth number," Beard writes. "Here he lays downwardly, in no uncertain linguistic communication, the principle that the offset and elemental business organisation of every government is economic" (Bristles 1913, p. 156).

Douglass Adair attributes the increased interest in the tenth number to Beard'due south volume. Adair also contends that Beard'due south selective focus on the issue of class struggle, and his political progressivism, has colored modern scholarship on the essay. According to Adair, Beard reads No. x as evidence for his belief in "the Constitution as an instrument of grade exploitation".[36] Adair's own view is that Federalist No. x should exist read equally "eighteenth-century political theory directed to an eighteenth-century problem; and ... ane of the peachy creative achievements of that intellectual movement that after ages accept christened 'Jeffersonian democracy'".[37]

Garry Wills is a noted critic of Madison's argument in Federalist No. 10. In his book Explaining America, he adopts the position of Robert Dahl in arguing that Madison'southward framework does not necessarily heighten the protections of minorities or ensure the mutual expert. Instead, Wills claims: "Minorities can make use of dispersed and staggered governmental machinery to clog, delay, tiresome down, hamper, and obstruct the majority. But these weapons for delay are given to the minority irrespective of its factious or nonfactious graphic symbol; and they tin can be used against the majority irrespective of its factious or nonfactious graphic symbol. What Madison prevents is not faction, but action. What he protects is non the common good but delay as such".[38]

Application [edit]

Federalist No. 10 is sometimes cited equally showing that the Founding Fathers and the constitutional framers did not intend American politics to exist partisan. For instance, U.Southward. Supreme Court justice John Paul Stevens cites the paper for the statement that "Parties ranked loftier on the listing of evils that the Constitution was designed to bank check".[39] Justice Byron White cited the essay while discussing a California provision that forbids candidates from running equally independents within i year of holding a partisan amalgamation, saying, "California manifestly believes with the Founding Fathers that splintered parties and unrestrained factionalism may do meaning impairment to the fabric of authorities."[40]

Madison's argument that restraining freedom to limit faction is an unacceptable solution has been used by opponents of campaign finance limits. Justice Clarence Thomas, for case, invoked Federalist No. 10 in a dissent against a ruling supporting limits on campaign contributions, writing: "The Framers preferred a political system that harnessed such faction for good, preserving freedom while also ensuring adept regime. Rather than adopting the repressive 'cure' for faction that the majority today endorses, the Framers armed individual citizens with a remedy."[41]

References [edit]

- ^ Epstein, p. 59.

- ^ Manweller 2005, p. 22.

- ^ Gustafson 1992, p. 290.

- ^ Bernstein, pp. 11–12, 81–109.

- ^ Woods, Idea, p. 104.

- ^ Stewart, p. 182.

- ^ Yates. [1]

- ^ For case, the important Anti-Federalist authors "Cato" and "Brutus" debuted in New York papers on September 27 and October 18, 1787 respectively. See Furtwangler, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Brawl, p. xvii.

- ^ Dates and publication data at "The Federalist", Constitution Society. Accessed January 22, 2011.

- ^ Kaminski and Saladino, Vol XIV, p. 175.

- ^ Adair, pp. 44–46. See too "The Federalist Papers: Timeline", SparkNotes. Accessed January 22, 2011.

- ^ Ford, p. forty.

- ^ Throughout Storing, for case, and relied upon by De Pauw, pp. 202–204. For Brawl, p. xlvii, information technology is the "authoritative edition" and "still stands as the near complete scholarly edition".

- ^ Federalist No. ten. p. 56 of the Dawson edition at Wikisource.

- ^ a b c d Dawson 1863, p. 58.

- ^ Cohler, pp. 148–161.

- ^ Adair, pp. 93–106.

- ^ Federalist No. 10. p. 56 of the Dawson edition at Wikisource.

- ^ Federalist No. 10. p. lx of the Dawson edition at Wikisource.

- ^ Federalist No. 10. p. 57 of the Dawson edition at Wikisource.

- ^ a b c Federalist No. 10. p. 62 of the Dawson edition at Wikisource.

- ^ Federalist No. 2. pp. 7–8 of the Dawson edition at Wikisource.

- ^ See the accounts by, and conclusions of, Storing, Vol 1, pp. 102–104, Kaminski, p. 131, pp. 309–310, and Forest, Creation, p. 489. De Pauw, pp. 290–292, prefers Abraham Yates.

- ^ Cato, no. 3. The Founders' Constitution. Volume i, Affiliate four, Document xvi. University of Chicago Press. Retrieved Jan 22, 2011.

- ^ Bribe, Roger 50. "Economics of the Civil War". Economic History Clan. August 24, 2001. Referenced November 20, 2005. Citing Bristles; Hacker; Egnal; Bribe and Sutch; Bensel; and McPherson, Bribe notes that "regional economical specialization ... generated very stiff regional divisions on economic issues ... economic changes in the Northern states were a major cistron leading to the political collapse of the 1850s ... the sectional splits on these economic issues ... led to a growing crisis in economic policy".

- ^ Letter past Madison to Jefferson, October 24, 1787. "James Madison to Thomas Jefferson". The Founders' Constitution. Book i, Chapter 17, Certificate 22. University of Chicago Printing. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- ^ Cohler, p. 151.

- ^ Letter by Benjamin Rush to Richard Price, October 27, 1786. "Benjamin Blitz to Richard Price". The Founders' Constitution. Volume i, Chapter 7, Certificate vii. Academy of Chicago Printing. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- ^ Montesquieu, Spirit Of Laws, ch. 16. vol. I, book 8, cited in Brutus, No. 1. The Founders' Constitution. Book 1, Affiliate four, Document fourteen. University of Chicago Press. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- ^ Yates is replete with examples.

- ^ Brutus, No. 1. The Founders' Constitution. Volume 1, Chapter four, Certificate 14. University of Chicago Press. Retrieved Jan 22, 2011. "History furnishes no case of a gratuitous republic, whatsoever thing like the extent of the United states. The Grecian republics were of small extent; and so likewise was that of the Romans. Both of these, it is true, in procedure of time, extended their conquests over large territories of state; and the consequence was, that their governments were inverse from that of free governments to those of the most tyrannical that ever existed in the world".

- ^ Adair, p. 110.

- ^ "The People'southward Vote", ourdocuments.gov, National Athenaeum and Records Administration. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- ^ Epstein, p. 59.

- ^ Adair, pp. 120–124. Quotation at p. 123.

- ^ Adair, p. 131.

- ^ Wills, p. 195.

- ^ California Democratic Party v. Jones, 530 U.Southward. 567, 592 (2000) [2]

- ^ Storer v. Brown, 415 U.South. 724, 736 (1974) [3]

- ^ Nixon v. Shrink Missouri Authorities PAC, 528 U.Southward. 377, 424 (2000) [4]

Secondary sources [edit]

- Adair, Douglass. "The Tenth Federalist Revisited" and "'That Politics May Be Reduced to a Scientific discipline': David Hume, James Madison and the Tenth Federalist". Fame and the Founding Fathers. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1998. ISBN 978-0-86597-193-six New York: WW Norton & Co, 1974 ISBN 978-0-393-05499-vi

- Ball, Terence. The Federalist with Letters of "Brutus". Cambridge University Printing: 2003. ISBN 978-0-521-00121-ii

- Beard, Charles A. An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States. New York: The MacMillan Company, 1913.

- Bernstein, Richard B. Are We to Exist a Nation? Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987. ISBN 978-0-674-04476-0

- Cohler, Anne. Montesquieu'southward Comparative Politics and the Spirit of American Constitutionalism. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1988. ISBN 978-0-521-36974-9

- Dawson, Henry B., ed. The Fœderalist: A Collection of Essays, Written in Favor of the New Constitution, As Agreed Upon by the Fœderal Convention, September 17, 1787. New York: Charles Scribner, 1863.

- Epstein, David F. The Political Theory of The Federalist. Chicago: University of Chicago Printing, 1984. ISBN 978-0-226-21300-2

- Furtwangler, Albert. The Authorization of Publius: A Reading of the Federalist Papers. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Printing, 1984. ISBN 978-0-8014-1643-9

- Grant DePauw, Linda. The Eleventh Pillar: New York Land and the Federal Constitution. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1966. ISBN 978-0-8014-0104-6

- Gustafson, Thomas (1992). Representative Words: Politics, Literature, and the American Language, 1776–1865. Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0-521-39512-0.

- Kaminski, John P. George Clinton: Yeoman Political leader of the New Commonwealth. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1993. ISBN 978-0-945612-17-9

- Manweller, Mathew (2005). The People Vs. the Courts: Judicial Review and Directly Democracy in the American Legal System . Academica Press, LLC. p. 22. ISBN978-i-930901-97-ane.

- Morgan, Edmund S. * "Safety in Numbers: Madison, Hume, and the 10th 'Federalist,'" Huntington Library Quarterly (1986) 49#2 pp. 95–112 in JSTOR

- Stewart, David O. The Summer of 1787: The Men Who Invented the Constitution. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007. ISBN 978-0-7432-8692-3

- Wills, Garry. Explaining America: The Federalist. New York: Penguin Books, 1982. ISBN 978-0-14-029839-0

- Forest, Gordon. The Cosmos of the American Republic, 1776–1787. Chapel Hill, NC: UNC Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0-8078-4723-vii

- Woods, Gordon. The Idea of America: Reflections on the Nascence of the U.s.. New York: Penguin Press, 2011. ISBN 978-one-59420-290-2

Primary sources [edit]

- Hamilton, Alexander; Madison, James; and Jay, John. The Federalist. Edited by Jacob Due east. Cooke. Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 1961. Wesleyan 1982 edition: ISBN 978-0-8195-6077-iii

- Hamilton, Alexander; Madison, James; and Jay, John. The Federalist. Edited by Henry B. Dawson. Morrisania, New York: Charles Scribner, 1863. Accessed January 22, 2011.

- Hamilton, Alexander; Madison, James; and Jay, John. The Federalist. Edited past Paul Leicester Ford. New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1898.

- Kaminski, John P. and Saladino, Gaspare J., ed. The Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution. Madison: State Historical Order of Wisconsin, 1981. ISBN 978-0-87020-372-5

- Storing, Herbert J.; Dry, Murray, ed. The Consummate Anti-Federalist. Vols 1–7. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981. ISBN 0-226-77566-half dozen

- Yates, Robert. Notes of the Clandestine Debate of the Federal Convention of 1787. Washington, D.C.: Templeman, 1886. Accessed January 22, 2011.

- "Storer v. Dark-brown, 415 U.Southward. 724 (1974)". Findlaw . Retrieved October 1, 2005.

- "Nixon v. Shrink Missouri Authorities PAC, 528 U.S. 377 (2000)". Findlaw . Retrieved August 23, 2005.

- "California Democratic Party v. Jones, 530 U.S. 567 (2000)". Findlaw . Retrieved Baronial 23, 2005.

External links [edit]

- Text of The Federalist No. x: congress.gov

- Online text of Brutus, no. 1, Academy of Chicago.

- Online text of Cato, no. 3, same source every bit to a higher place

hatchermansampard1945.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Federalist_No._10#:~:text=Madison%20defines%20a%20faction%20as,community.%22%20He%20identifies%20the%20most

0 Response to "what is a faction according to federalist 10"

Post a Comment